At long last an exhibit of Parajanov’s artworks from the Sergei Parajanov Museum in Yerevan has come to New York City. Entitled Sergei Parajanov: The Creator, the exhibit runs through June 30, 2014 at Gilbert Albert, 43 West 57th Street, in the 2nd floor gallery space.

Sponsored by the Russian American Foundation and IBEF, Inc., this exhibit consists of 35 pieces, including several of the main highlights of the Parajanov Museum collection. They include paintings, sketches, collages, assemblages, dolls, and hats, ranging from the 1950s to the end of his life.

Below is the text that I wrote for the exhibition catalog (reproduced with permission):

Sergei Parajanov (1924-1990) unquestionably has played a major role in global film culture, thanks to such dazzling and stylistically innovative works as Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (Ukraine, 1965), The Color of Pomegranates (Armenia, 1969), The Legend of the Surami Fortress (Georgia, 1984), and Ashik-Kerib (Georgia and Azerbaijan, 1988). He was also a prolific and accomplished artist in other media. By far the largest and richest collection of Parajanov’s artworks is housed at the Sergei Parajanov Museum in Yerevan. This represents the first exhibition from the Parajanov Museum collection in New York, a signal event in the realms of both art and cinema.

Parajanov’s drawings, collages, and assemblages not only shed light on the creative process and underlying thematic concerns in his films, but they also demand attention on their own terms. While a number of other filmmakers have created artworks as an avocation, Parajanov offers a unique case both in terms of the sheer quantity of works that he created and their overall artistic achievement.

Coming from the sizable Armenian community in Tbilisi, Georgia, Parajanov grew up immersed in the rich cultural environment of the South Caucasus. His father, Iosif Parajanov, ran a commission shop for antiques and thus imparted a lifelong fascination with antiques and art objects in the young boy. His mother Siran played the piano. Thus, it is not surprising that from the start Parajanov displayed an aptitude for the arts. Before enrolling in Igor Savchenko’s film directing workshop at the VGIK (the All-Union State Institute of Cinematography), he studied voice at the Tbilisi Conservatory, as well as violin and dance. During his years at the VGIK (1945-1952) he studied art history and drawing as part of the curriculum; his earliest surviving artworks date from that period or slightly later.

Over time, artworks occupied an increasingly significant place in Parajanov’s creative imagination. During the 1970s and early 1980s—when he was designated persona non grata by the Soviet authorities, imprisoned in Ukraine (1973-1977), and denied the opportunity to make films—drawings, collages, and assemblages became his primary outlet. If in a very real sense glasnost originated in Georgia with the production of Tengiz Abuladze’s film Repentance (1984, released 1987) and Parajanov’s return to filmmaking with The Legend of the Surami Fortress (1984, released 1985), perhaps another sign of it was the first public exhibition of Parajanov’s artworks, which took place in Tbilisi in January 1985. Armenia also hosted an exhibition in 1988 at the Museum of Folk Art in Yerevan, leading to the construction of the Sergei Parajanov Museum in that city.

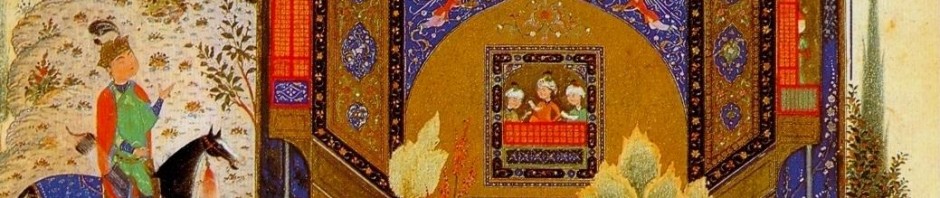

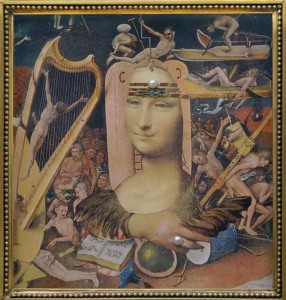

By turns whimsical, provocative and surreal, these pieces reflect Parajanov’s free spirit, his gift for caricature, and his penchant for transforming mundane objects and situations into something magical. They further recall some of his primary artistic influences, which range from Armenian and Persian miniatures (often “quoted” as fragments in his collages), religious icons, folk art, painters from the South Caucasus such as Pirosmani and Hakob Hovnatanyan, and the Italian Renaissance. Of special note is a series of collages that radically transform the Mona Lisa. Besides paintings, drawings, collages and assemblages, Parajanov created a large number of dolls and hats. In their cheeky appropriation of found objects and reproductions, his collages and assemblages express a distinctly postmodern sensibility. They also offer a glimpse into his private memories and the people he knew and admired.

When friends and strangers alike visited Parajanov’s family home in Tbilisi, which was crammed with his own creations, he liked to transform it into a space for Andy Warhol-style “happenings.” As a visitor to this exhibition, you are invited to join in his games.

Where may one obtain a copy of the catalogue?

I am not 100% certain, but you might try contacting one of the sponsors: the Russian American Foundation (http://russianamericanfoundation.org/) or IBEF, Inc.