The Brooklyn Rider string quartet performance at Emory’s Schwartz Center (April 12, 2013) offered a compelling demonstration of why live performance still matters, and how musicians can keep the Western art music tradition vital and exciting through creative programming and engaged performances. Brooklyn Rider is fun to watch and interacts well with the audience, but they are also a very talented ensemble that has mastered a wide range of styles. The quartet consists of: Johnny Gandelsman (violin), Colin Jacobsen (violin), Nicholas Cords (viola), Eric Jacobsen (cello).

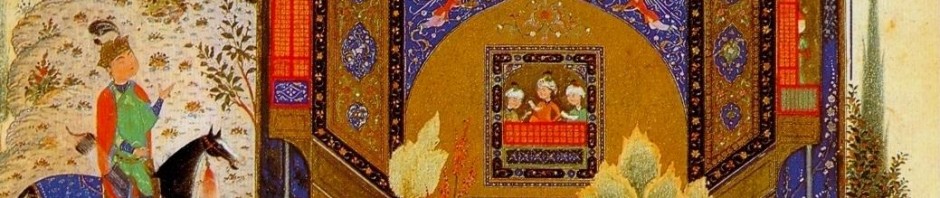

The first half of the concert, derived from Brooklyn Rider’s soon-to-be-released album Walking Fire, contained music with a marked ethnic component. Johnny Gandelsman showed off his flair for klezmer-style playing in Budget Bulgar by Lev Zhurbin. For me, hearing this piece brought to mind the underlying connection between klezmer and Roma lăutari music, since I had recently watched the Soviet-era Moldovan film Lautari (1972) by Emil Loteanu. It has been a while since I heard Béla Bartók’s String Quartet No. 2. I was struck by how modern this work still sounds, with its challenging structure and a style of writing for strings that differs radically from quartets of the Romantic era, though it is ravishingly beautiful in its own right. The first half of the concert closed with Colin Jacobsen’s Three Miniatures for String Quartet, which evoked Persian themes. While the three pieces did use Persian-style improvisations in the melodies, they thankfully avoided any clichéd Orientalism. In general, the new compositions in the first half tended to rely heavily on melodies elaborated over quasi-ostinato accompaniments; this programming choice risked becoming repetitious, though the compositions themselves were lively and enjoyable.

The second half of the concert was derived from Brooklyn Ryder’s album Seven Steps: a group composition entitled Seven Steps and its intended companion piece, Beethoven’s String Quartet Op.131 in C sharp minor. Compared to the new compositions in the first half, Seven Steps showed a broader range of compositional styles, including (if I heard correctly) minimalism and Ligeti-style microtonal polyphony. In a way, the piece might be understood as a kind of tour through twentieth century music history.

In truth, I was drawn initially to the program by the opportunity to see a live performance of the Beethoven String Quartet Op.131, which is one of Beethoven’s most perfect compositions and arguably the pinnacle of all string quartet repertoire, with its profoundly conceived structure and sublime interplay between the four instruments. The work can present a quandary for contemporary performers, since it has been so widely recorded that it is difficult to come up with a fresh interpretation that won’t be compared negatively to the many classic recordings that audience members may have heard already. As they acknowledged in the program, Brooklyn Rider was inspired partly by an older performance style that uses less vibrato and somewhat more liberal portamento, namely pre-World War II quartets such as Busch, Capet and Rosé. In fact they did not push this interpretive strategy too far, so the performance did not come across as willfully eccentric. They also tended to use relatively fast tempos throughout. The opening fugue (Adagio ma non troppo e molto espressivo) was perhaps too fast and they could have pulled more expressiveness from it, but the rest of the quartet came off very well indeed. I liked how the cellist conveyed humor in some of the pointed pizzicati in the central theme-and-variations movement and the abrupt opening phrase of the fifth movement. This is precisely the sort of thing that is possible in live performances but may not get conveyed adequately in a recording. The finale was simply outstanding, a vividly dramatic and rhythmically forceful reading that capped the work in exactly the right way.

Incidentally, Brooklyn Rider’s recording of Beethoven’s Op.131 on the Seven Steps album is also definitely worth a listen, as is the album as a whole. In the opening fugue they use even less vibrato than what I heard in the live performance. Combined with the fast tempo, it seems to emphasize the fugue’s connections with early music. This is a genuinely interesting idea, considering Beethoven’s references to Baroque and earlier music throughout his late compositions, including the use of the Lydian mode in the Op.132 string quartet and the quasi-sarabande as the main theme in the last movement of the Op.109 piano sonata. While I do feel that as result the fugue loses some of its wrenching emotional depth–Wagner reportedly said that it “reveals the most melancholy sentiment expressed in music”–they deserve credit for thinking deeply and creatively about Beethoven’s composition as a whole. The recording space is a shade too resonant for my taste, but nonetheless the recording is unusually well-engineered, enabling one to hear the individual instruments very clearly. While listening to it I picked up on many details in the instrumentation that are normally apparent only by following the written score. Considering the absurd bounty of Beethoven recordings out there, it says something that I look forward to hearing Brooklyn Rider’s interpretation again in the future, along with the rest of the album.