The Film Society of the Lincoln Center is showing the cream of the crop of Ukrainian cinema on September 7-12 in a series entitled “Capturing the Marvelous: Ukrainian Poetic Cinema.” All of these films are nothing short of dazzling and some of them are not readily accessible on DVD with English subtitles, so if you live in New York you would be crazy not to catch them on the big screen. I write about most of these films in my forthcoming book on Sergei Parajanov, so they are still very much fresh in mind.

Broadly speaking, Ukrainian poetic cinema tends to focus on Ukrainian identity and culture (especially folklore), employs a painterly visual style and pushes the boundaries of film technique and narrative. The term “poetic” comes primarily from the films’ abundance of metaphors and symbols, but one can further extend the parallel with poetry as a literary genre and how many of the films use the language of cinema.

Generally, critics trace the origin of Ukrainian poetic cinema to the films of Alexander Dovzhenko. His silent films Zvenigora / Zvenyhora (1927) and Earth (1930) are readily available on video and are widely written about, so I do not need to belabor their virtues here. If there is an omission in the series, it is Dovzhenko’s first sound film, Ivan (1932), whose experiments in editing and sound likely influenced Ukrainian poetic filmmakers in the 1960s.

Sergei Parajanov’s Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964) was his first international success and his masterpiece alongside the Armenian production The Color of Pomegranates (1969). Easily the most widely seen and discussed Ukrainian film after Dovzhenko’s Earth, it initiated the Ukrainian poetic cinema revival of the 1960s, which was based out of the Dovzhenko Film Studio in Kyiv. As with Shadows, the majority of these Sixties films were set in the past or in rural locales, a trope which the filmmakers used to explore questions of Ukrainian history and identity.

Yuri Illienko (1936-2010), the director of photography for Shadows, subsequently became a major director in his own right. His brilliant debut, A Well for the Thirsty (1965, also translated as A Spring for the Thirsty), based on a poetic script by Ivan Drach, was surely one of the most daring formal experiments ever produced in Soviet cinema. Virtually plotless and lacking dialogue for large portions of its running time, the film concerns an old man who lives alone since his wife has passed away and his sons have departed. The village where he lives is surrounded by parched soil, but the water from his well sustains the villagers and, years earlier, soldiers who passed through during the war. The man envisions a beautiful young woman, presumably his wife at a younger age, carrying pails of water. The densely textured film uses repeated visual and audio motifs to create a structure akin to a musical composition. Continuing the experiments with film stock that Illienko began while working on Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, the film uses special high-contrast stock, at times pushed even further so that the stark black-and-white imagery looks like an engraving or ink drawing. The sound track is a complex audio collage of recited poetry, song fragments, cries and sound effects such as ringing bells; no doubt it served as a major source of inspiration for Parajanov’s use of sound in The Color of Pomegranates. The film ran afoul of the authorities and was banned until 1987, when it was finally released along with a number of other long-banned Soviet films.

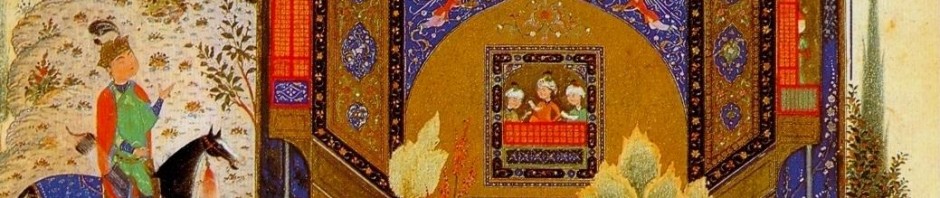

Illienko’s second feature, The Eve of Saint John (1968) is an ambitious adaptation of Gogol’s story of the same name. (Arguably, a better translation would be The Eve of Ivan Kupala, since it refers to the summer festival that originated as a pagan fertility rite.) The film’s style and imagery attempt to recreate the phantasmagorical world of Gogol’s prose in cinematic terms through jump cuts and other forms of trick editing, exaggerated Ukrainian decorative motifs, and distortions of scale and perspective. Beyond that, Illienko tries to make the film into a meditation on Ukrainian history; at one point, the main character of Pidorka (Larisa Kadochnikova) is caught up in the Mongol invasion of the thirteenth century and subsequently witnesses Catherine the Great and Potemkin’s legendary tour of facade-villages in the Ukrainian countryside. Ultimately, the film seems overburdened with trick effects and was coolly received by Soviet critics, but it remains memorable for its extraordinary wealth of surrealistic imagery. It is an absolute must on the big screen.

Illienko’s greatest commercial and critical success was by far White Bird with a Black Mark (1970), which won the Golden Prize at the Moscow Film Festival in 1971 and drew 10.5 million admissions in the Soviet Union as a whole. Co-written by Illienko and its star Ivan Mykolaichuk (the star of Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors), the film concerns an impoverished Hutsul family whose loyalties are divided between the Soviets and the Romanians during World War II. It deploys a straightforward narrative and pointedly orthodox representations of negative figures such as the band of Ukrainian nationalist insurgents and the priest. But it also contains many of Illienko’s characteristic stylistic touches, including jump cuts, 360-degree tracking shots, and telephoto camerawork that strongly recalls Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.

Leonid Osyka (1940-2001) may not be as well known in the West as Parajanov or Illienko, but The Stone Cross (1968) stands alongside their works on its own terms. Based on a script by Ivan Drach and adapted from the writings of Vasyl Stefanyk, it depicts an old man in Western Ukraine who tires of working his barren plot of land and decides to emigrate with his family to Canada. On the eve of his departure, he catches a thief on his farm and plans to kill him, but succumbs to compassion while his neighbors stand fast in their rigid code of honor. As a memorial to his life in his homeland, he leaves a stone cross on a hill. Especially noteworthy is the farewell party, which takes up about half of the 80-minute film. In a series of long takes, the camera circles around the villagers, following the old man while he approaches various individuals, speaks, and offers to drink toasts with them. The overall texture of the film is deliberately spare compared to the kaleidoscopic quality of Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors or The Eve of Ivan Kupala, and it depends more heavily on dramatic dialogue than A Well for the Thirsty. Still, a great deal of the film’s sense is conveyed through its expressive imagery, including intense close-ups of the villagers’ time-ravaged faces and the heavily flattened, almost abstract images of the countryside.

The Ukrainian poetic cinema revival continued through the early 1970s, though some of the films were banned or shelved, and others received only limited distribution outside of Ukraine. In May 1974, less than a month after Sergei Parajanov’s imprisonment on politically motivated charges of homosexuality, Volodymyr Shcherbytsky, the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine, publicly condemned Ukrainian poetic cinema and declared it “overcome.” Despite this, Yuri Illienko continued to make innovative works, though his first three films remained his strongest. Leonid Osyka’s subsequent output was more uneven. Still, the films shown in this series represent a major contribution to world cinema and the best postwar Ukrainian films alongside those of the Odessa-based Kira Muratova.

Thanks for the post – great to see that these rare films will be shown. Is there any news of when the Paradjanov book that you mention will be published and who by? Am very much looking forward to reading it when it’s published.

You’re welcome! It’s a shame that I can’t be in New York for this series, but I’ve seen all of the films except for ZVENIGORA in 35mm and can attest that they are spectacular. Since Seagull Films is handling the series as a touring package, they will probably show at other cities in the US, though not in England unless something separate is arranged.

The Parajanov book is under contract with the University of Wisconsin Press and is slated for release (at this point) in Fall 2013, though of course it is still very early so the date may change.

P.S. – I really liked your latest blog entry on Marlen Khutsiev. Agreed, he is very much an underappreciated filmmaker. Interestingly, he studied at the VGIK under Igor Savchenko along with Parajanov, Kulidzhanov, and Alov and Naumov, among others. One could argue that it was that crop of filmmakers who really initiated the Thaw.

Thanks, and good luck with the book – I’m looking forward to reading it when it comes out- would be interesting to hear what Khutsiev and Paradjanov thought of each other. Over the summer I met an artist in Odessa (Stepan Khimochka) who told me he had worked with Paradjanov – although he told me they worked together for just a short time- am not sure on exactly what project it was though as he didn’t give me many details and he went on to talk about something else. I must admit I was bursting with curiosity to know more about his time working with Paradjanov.

I was fortunate enough to see Leonid Osyka’s *The Stone Cross* at its Lincoln Center screening this past Wednesday, along with my mom, who was born in Ukraine. We were taken both by the formal beauty and the elegiac tone of the film. Equally, we were struck by its timeless quality–it hardly seems marked by the era in which it was made. Although I have seen and deeply admire many of the films included in this series, Osyka’s work was new to me. Thank you for your illuminating and thoughtful reflections on this film, and on the “Capturing the Marvelous: Ukrainian Poetic Cinema” series overall. Please let me know when your new book on Parajanov will be out in print, as I look forward to reading it.

~Irena

P.S. I did a quick internet search to see how many of the films in the series are available on DVD through North American distributors, but had no luck, apart from *Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors,* and other works by Parajanov that we already own on DVD. We also own a multi-region DVD player. I would be grateful for any suggestions that you might have in regard to tracking down DVDs of Ukrainian films.

Irena, I’m glad that you were able to see The Stone Cross at the Lincoln Center! Of the films by Osyka that I’ve seen that is easily the best, though Zakhar Berkut is also striking as a historical film and it’s based on a classic novel by Ivan Franko. Ukrainian films are still fairly difficult to obtain – very few are available through North American distributors, though Ruscico has released some with subtitles. You can get them through online stores such as russiandvd.com. There are also some Ukrainian bookstores, especially in Canada, that sell DVDs but most of those lack subtitles and the transfers often don’t look that great. The company Mr. Bongo has released Dovzhenko’s Zvenyhora, Arsenal and Earth on DVD in England, and they are new transfers. The Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Centre in Kyiv has also released some subtitled box sets of Ukrainian films for institutional use, including most of the films in the Lincoln Center series. I don’t know whether they make those sets available to individuals.