As anyone familiar with Sir Salman Rushdie’s works must know by now, he is a great cinephile in addition to being a great writer. As the Distinguished Writer in Residence at Emory, this semester he is curating a series entitled “Great Works of Fiction Made Into Great Films,” sponsored by the Department of English, the Department of Media Studies, and the Office of the Provost at Emory. Monday night’s film (Feb. 21) was Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955), in a restored 35mm print from the Academy Film Archive.

After the screening Rushdie commented that one important difference between the film and Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay’s novel was that the novel went further in its depiction of the brutal conditions of life in rural Bengal. Among other things, the film left out the pervasive domestic violence which many women characters suffered. Rushdie argued that Ray’s film adaptation was ultimately even better than the novel, which is a literary masterpiece in its own right; one aspect in particular that he singled out is the film’s extraordinary visual lyricism.

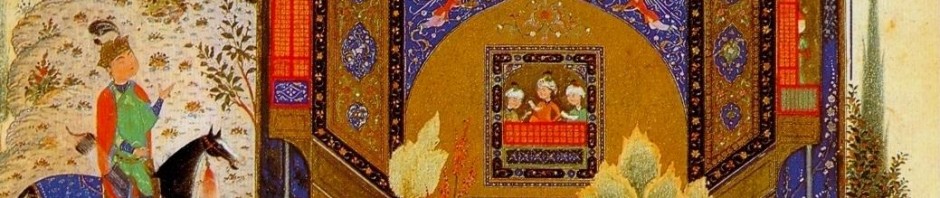

I have to agree: seeing the film in 35mm confirms that Pather Panchali surely stands among the greatest films ever made, together with the other two films in Ray’s trilogy. The ending is almost unbearably heartbreaking–it never fails to reduce me to tears no matter how often I see it. But the film’s visual lyricism is also critical to the cumulative effect of the trilogy as a whole: in the first film, the lyrical passages don’t just soften a story that would have been otherwise too bleak for most viewers. They’re important because they help us share Apu’s emergence into consciouness and the development of his poetic sensibility as a future writer. Although it is a very different kind of film, its treatment of a poet’s childhood impressions–or rather, its depiction of how the world shapes a poet’s consciousness–reminds me a bit of Parajanov’s The Color of Pomegranates. The other aspect I find astonishing is Ray’s handling of nonprofessional actors, which at least equals or possibly surpasses similar efforts by Renoir and the Italian neorealism movement. There is not a single false note in the entire cast.

The other screenings in the series are John Huston’s The Dead (February 28), Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt (March 14) and Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita (March 21). The screenings are free and open to the public, and the venue (White Hall 208 on the Emory campus) benefits greatly from a pair of newly installed 35mm projectors. The image positively gleamed Monday night.